Sunlight on Brownstones

Hopper, Edward

1956

Artwork Information

-

Title:

Sunlight on Brownstones

-

Artist:

Hopper, Edward

-

Artist Bio:

American, 1882–1967

-

Date:

1956

-

Medium:

Oil on canvas

-

Dimensions:

30 3/8 x 40 1/4 in.

-

Credit Line:

Wichita Art Museum, Roland P. Murdock Collection

-

Object Number:

M148.57

-

Display:

Currently on Display

About the Artwork

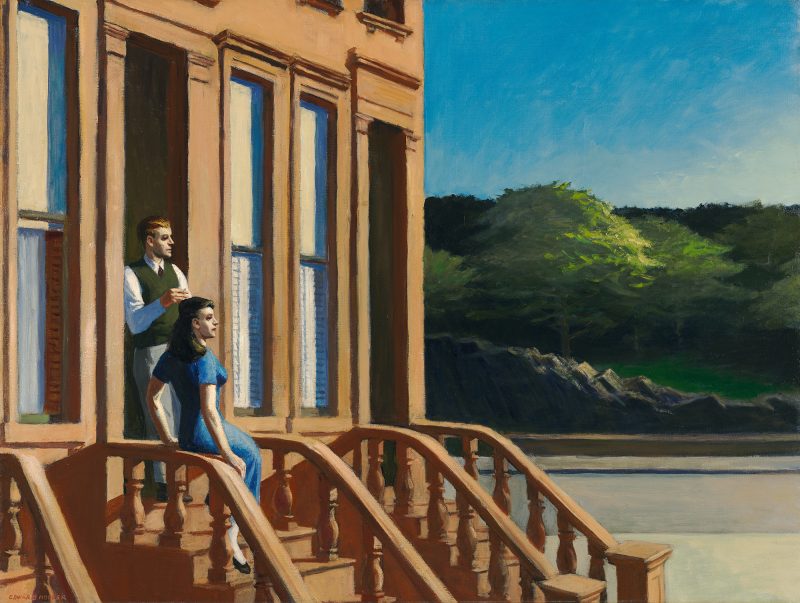

“Maybe I am not very human,” Edward Hopper mused in 1946. “What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.”1 Hopper pursued this modest aspiration with renewed vigor during the last decades of his career, suggested by the title of Sunlight on Brownstones as well as Morning Sun (1952), Second Story Sunlight (I960), and Sun in an Empty Room (1963).

In the left half of Sunlight on Brownstones, a smartly dressed couple lounge on the stoop of a brownstone apartment. They appear locked into place by the strict rhythm of vertical lines formed by the windows, doorways, and railings. To the right, the green trees of an undeveloped grove seem to retreat from the advancing tide of civilization. Hoppers brushstrokes underscore this implied dissonance: on the right side of the painting, the trees are formed by loose, fluid brushstrokes that counteract the meticulously painted, rigidly architectonic forms on the left. Gail Levin has suggested that the composition for Sunlight on Brownstones shares a striking similarity to Rembrandt’s etching The Good Samaritan, which also depicts two figures standing in a doorway of a building that recedes into space in a similar fashion.2 In her diary entry for 10 February 1956, Hoppers wife, Jo, noted that her husband “hasn’t started his new canvas yet [Sunlight on Brownstones], goes over his sketches, gazes at book of Rembrandt reproductions, reads this & that.”3

The couple on the stoop appear to gaze upon something beyond the painting’s right edge, begging the question of their interest. The answer appears to lie outside the paintings frame, both literal and temporal. Like a movie still, Sunlight on Brownstones seems to have been removed from a larger narrative.4 Hopper frustrates any attempt to create a cohesive account from the clues left in the painting. On one occasion, Jo Hopper suggested that a female figure at a window in another painting was checking the weather. Her suggestion earned her a stern rebuke from the artist: “You’re making it Norman Rockwell. From my point of view, she’s just looking out the window.”5

Hopper’s stringent aversion to narrative and anecdote first manifested itself, ironically, when the artist worked as an illustrator and commercial artist from 1906-24. His editors’ demands for dramatic illustrations clashed with Hopper’s commitment to a less theatrical approach. “I was always interested in architecture,” the artist once remarked, “but the editors wanted people waving their arms.”6 Far from gesticulating wildly, the man and woman in Sunlight on Brownstones do not gesture or even interact at all. Instead, they seem to look expectantly toward the sun, as if searching for an answer to an unspoken question.

1. Original notation in the Lloyd Goodrich papers, dated 20 April 1946, quoted in Matthew Baigell, “The Silent Witness of Edward Hopper,” Arts 49 (September 1974): 33.

2. Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 496.

3. Jo Hopper diary entry for 10 February 1956, quoted in Levin, 496.

4. Robert Hobbs, Edward Hopper (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 16.

5. Hopper, quoted in “Gold for Gold,” Time 65, 30 May 1955, 72.

6. Hopper, quoted in Hobbs, 79.