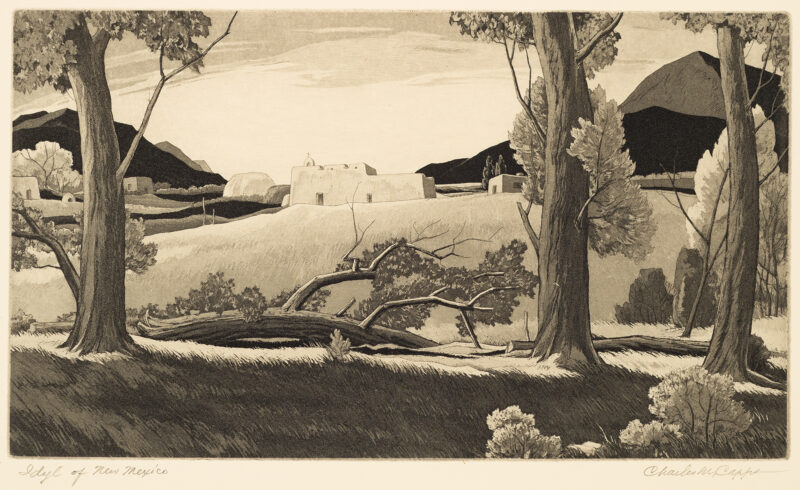

Idyl of New Mexico

Capps, Charles M.

1965

Artwork Information

-

Title:

Idyl of New Mexico

-

Artist:

Capps, Charles M.

-

Artist Bio:

American, 1898–1981

-

Date:

1965

-

Medium:

Etching and aquatint

-

Dimensions:

7 x 12 3/16 inches

-

Credit Line:

Wichita Art Museum, Gift of Leta M. Smith

-

Object Number:

1988.27.33

-

Display:

Not Currently on Display

About the Artwork

Charles Capps was just one of legions of American artists who, since the beginning of the 20th century, have been attracted to the landscape and culture of the Southwest. The frequent portrayal of the Native Indian-Hispanic architecture in the imagery of the Taos and Santa Fe artists reveals much about their commitment to this region of the country.

Most of those who came had had substantial training in the history and techniques of painting and printmaking. Most had established careers as fine artists, art teachers, commercial artists, or they held great promise for success in those areas. All these artists, in the first half of the century, were conscious to some degree of the second-rate position held by American art in relation to that of the European avant-garde. They chafed under subtle pressures; one to be modern, to realize a vision of elemental, universal forms; another to be American, to resist the slavish impulse to imitate Europe and prove instead that American experience could generate greatness. The Southwest, in the parlance of European Surrealism, provided a “ready made” resolution to these conflicting pressures.

The adobe architecture of the Southwest belonged exclusively to the Americas. It was a product of native soil shaped by the unique historic confluence of ancient Indian cultures with the Renaissance era expansionism of Europe. The architecture could be called primitive in character. Primitivism was near and dear to the ideals of Modernism; primitive equates with universal in the sense of going back to origins; it also equates with modern in the sense of being pure, clean, no-frills functional. The American artist sensed that in the imperfectly rectangular adobe structures of the Southwest he had discovered a modern classic, a form from the American vocabulary, which expressed the eternal.