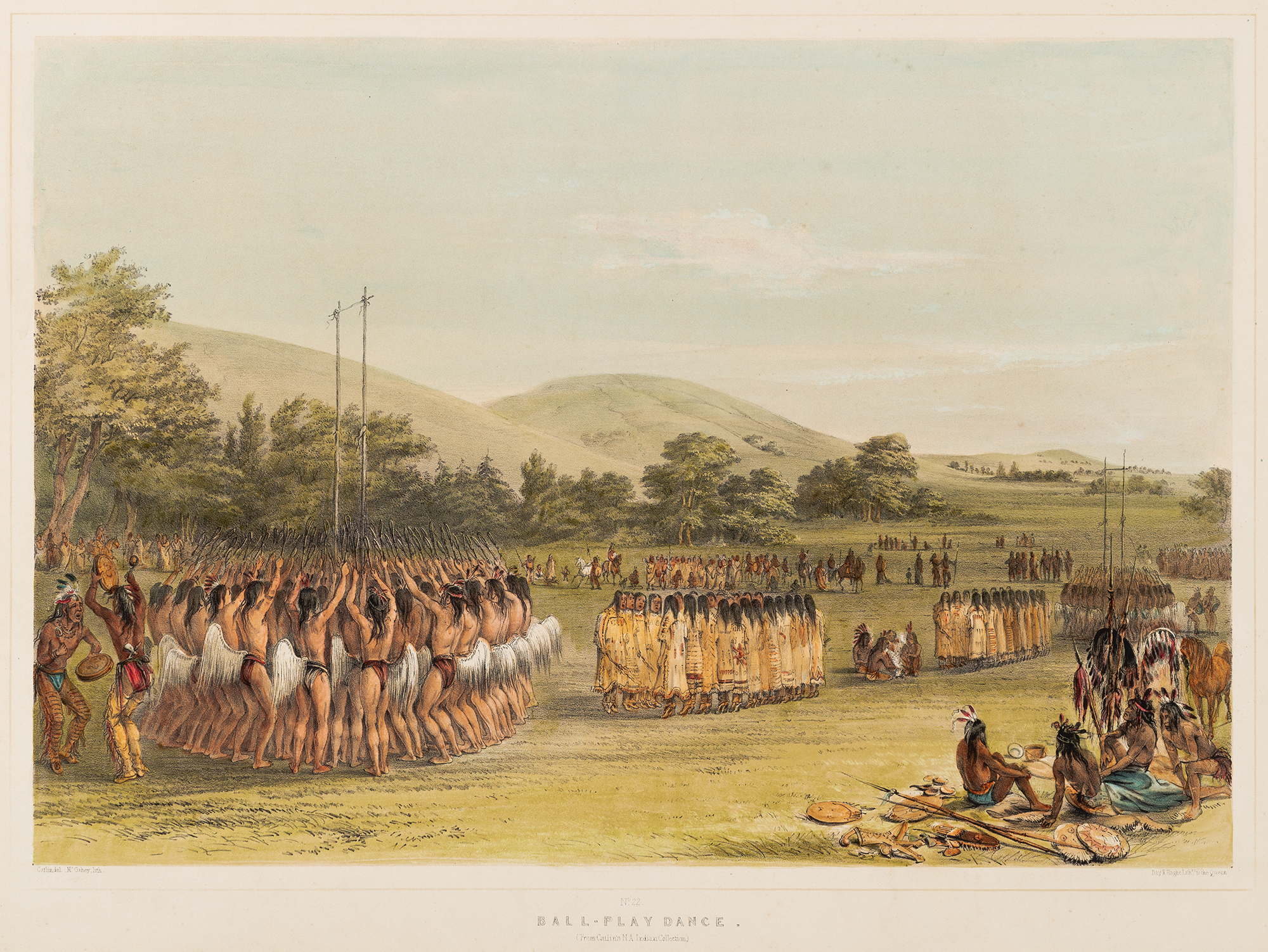

Ball-Play Dance, #22

Catlin, George

1844

Artwork Information

-

Title:

Ball-Play Dance, #22

-

Artist:

Catlin, George

-

Artist Bio:

American, 1796–1872

-

Date:

1844

-

Medium:

Hand-colored lithograph

-

Dimensions:

12 3/8 x 17 15/16 inches

-

Credit Line:

Wichita Art Museum, Museum purchase, Friends of the Wichita Art Museum, and funds from various donors

-

Object Number:

1978.95.2

-

Display:

Not Currently on Display

About the Artwork

The self-taught but internationally distinguished American artist, George Catlin, executed this scene about 1835. It is titled “Ball-Play Dance” and is from a portfolio consisting of 25 plates in which Catlin, following 8 years of extensive travel throughout the prairies and Rocky Mountains, documented the life and customs of the North American Indian tribes. Catlin had a sense of mission and advocated the creation of a vast Indian Reservation as a way of preventing the destruction of the race. He looked upon the Indian as the “Noble Knight of the Forest” and believed that in their natural environment, the Indians were happier than kings – a people who, in his own words. “. . . never fought a battle with white men except on their own grounds.”

Catlin was born in Pennsylvania. His western journeys began in 1832. It was about 1834, while at Fort Gibson (now Tulsa, Oklahoma) that he became interested in the Choctaw tribe and the many games they played. This work depicts the ceremonial preparation for the ball game. To the left, the players, each with two netted ball sticks recalling modern lacrosse sticks, are dancing around their two-poled field goal. In the distance to the far right, the opposing team performs the same ritual. Each player is without moccasins and wears only a breechclout, a beaded belt and an arch-shaped ceremonial tail of white horsehair. Standing in two separate groups along a line between the two teams are the women of each party, chanting – “. . to the Great Spirit . . soliciting his favor, and also encouraging the players to exert every power they possessed in the struggle that was to ensue.”

During his lifetime, Catlin found a more receptive audience in Europe than in America perhaps because of the then-prevailing ambiguous feelings toward the Indian in America. As a matter of fact, Catlin’s portfolio of which this work is a part, was published by Day & Haghe, a lithographic firm in London where Catlin exhibited for more than 10 years and where in a very real sense he invented the “wild west” show now popularly thought to be purely an American amusement.