Pit, The

Grosz, George

1946

Artwork Information

-

Title:

Pit, The

-

Artist:

Grosz, George

-

Artist Bio:

German, 1893–1959

-

Date:

1946

-

Medium:

Oil on canvas

-

Dimensions:

60 1/2 x 37 3/8 in.

-

Credit Line:

Wichita Art Museum, Roland P. Murdock Collection

-

Object Number:

M73.47

-

Display:

Not Currently on Display

About the Artwork

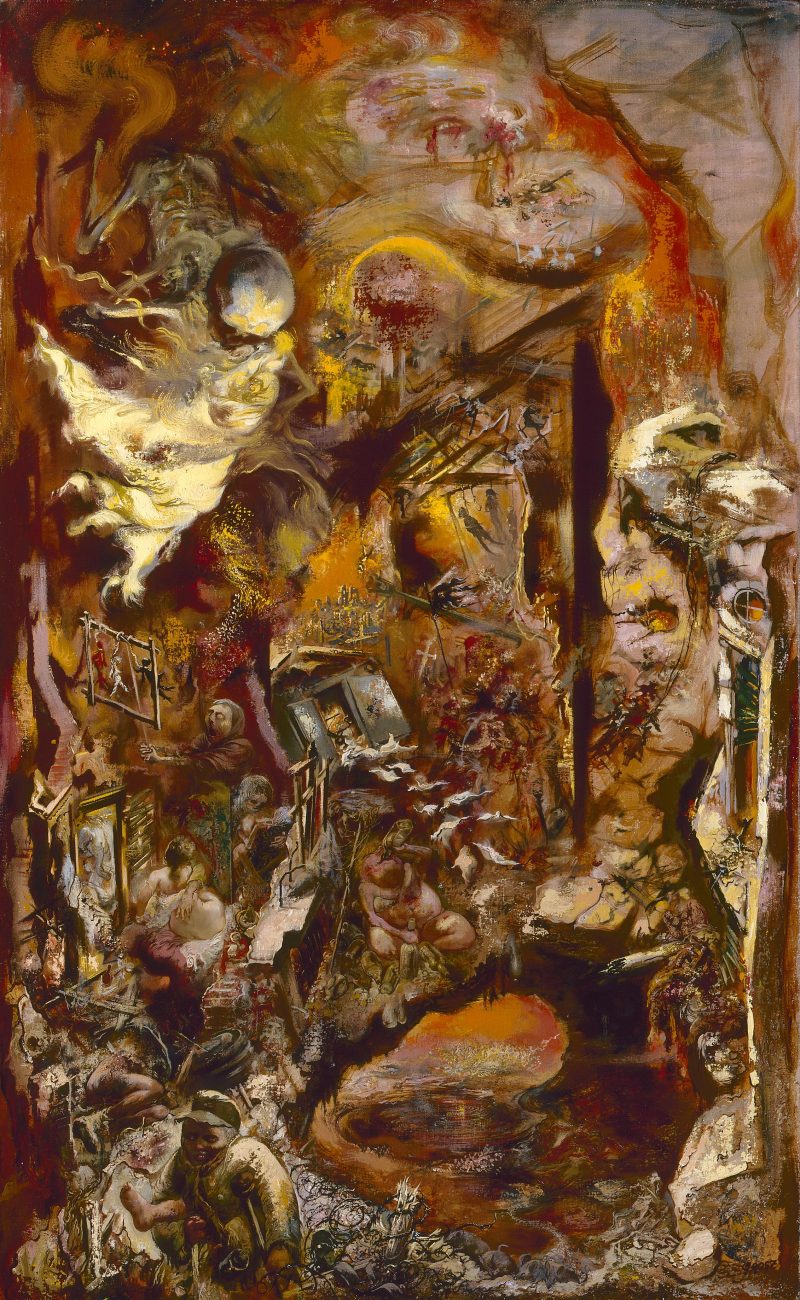

The Pit, Grosz’ most important painting, was also his favorite because it embraced in one canvas the story of his life. In the early forties Grosz was absorbed with the theme of the plight of the individual war. This painting is the culmination of his work during those years. The definitive statement on The Pit was made by John I. H. Baur on the occasion of a retrospective exhibition of the work of George Grosz held by the Whitney Museum of American Art in January and February 1954:

“Here is a truly fantastic vision with the scope and the nightmare reality of Bosch and a superbly integrated design that holds together all the elaborate symbolism of our unhappy times. Iconographically, the picture is fascinating. From the pit with its burning city, evil swarms upward into the world in the guise of a thousand rats, a long sinuous line of them with its front ranks just emerging in the foreground. At the left, the unknown soldier, half-crazed, carries his own missing leg under his arm. Above him is prostitution, a sensuous nude embraced by a headless and bodiless figure – a pair of anonymous arms. Nearby an emaciated mother and child personify starvation and a mad fanatic works the strings of red, white, and black puppets, the political taboos of our day. In the center, money, looking like winged doves, is scattered from a broken vault, near which the dead hang on a gibbet. Below, the eternal drunkard sits on a pile of empty bottles, while beside him a solitary figure, perhaps the artist himself stares at the scene from his barred prison. Over it all hover two apparitions: in the center the moon-like face of Mother Europa with blood at the corner of her mouth and her arm filled with struggling figures, at the left, death, as a skeleton, winging down with a fluttering, yellow-green shroud. The shattered house, which mounts high on the right, is not an impersonal ruin; to Grosz it is the house he never saw where his mother died in a bombing raid during the war.”

“The skill with which this elaborate symbolism has been woven into a single picture is impressive. Using a setting which suggest a crypt or grotto, Grosz has built up his incidents into restless, fluttering lines that dart forward and back, upward, and down like bats in a cavern. Big broken forms balance the multiplicity of detail and bridge the complicated system of level. At top and bottom the restless activity fades away into the mysterious depths of the sky and the pit. ‘The unformed, the nihilistic, the chaotic has a tremendous appeal for me,’ Grosz says, but he is also distrustful of this side of his nature, holding it, though only half-seriously, to be ‘a little dangerous, a little on the side of insanity.’ This is one of the few pictures in which he has yielded to it completely – and with what unexpected results. For here, despite the symbolism, is no anti-war tract, but almost a glorification of destruction, a kind of apocalypse painted, one would say, with love, not hate. The situation is a little like that of Kafka’s officer in the penal colony who fell so deeply in love with his own torture machine that he chooses to die on it himself. The parallel is not exact, for Grosz’ romanticism, despite his admiration for Kafka, is more disciplined and less morbid. A fairer comparison would be with some of the Last Judgments of Renaissance art or, more obviously, Bosch. Like these, The Pit is a moral painting with a strong weakness for demons.”

A critic commented on the symbolism of the painting in a Time magazine interview:

“In the lower center is a bloated, hog-faced cherub swilling strong drink (explains Grosz: ‘I come from a drinking family’). At his left, a fat buttocked nude is grasped by a hand that protrudes from no body; below lies a soft, naked torso and legs, which Grosz says represents the memory of his mother, killed in a Berlin air raid. In the lower left, a demented soldier hobbles on a crutch carrying his amputated left leg in the crook of his arm. That figure is a remembrance of the time Grosz spent in a mental military hospital during World War I (nervous breakdown following brain fever); one of his fellow patients was a German soldier who had lost his leg, and carried about a piece of wood in his arm. Over the whole broods the specter of ‘Mother Europe,’ gorged with blood of her dead.”1

- “Nothingness of our Time,” Time, vol. 63, no. 4, January 25, 1954, p. 80.